You need to create a part with complex curves and bends, but high-strength alloys are expensive, difficult to work with, and crack under pressure, causing costly failures and production delays.

The "workhorse" label isn't about strength; it's about versatility. Adding manganese to pure aluminum creates an alloy that retains exceptional formability and weldability, making it the default choice for complex shapes where high strength is an unnecessary cost.

I remember a client who was developing a series of intricate, lightweight housings for electronic equipment. They initially specified a 6061 alloy because they were familiar with its strength. However, their fabricators were struggling. The material was too hard, causing excessive tool wear and frequent cracking on the tight-radius bends. They were facing major production delays. We looked at the design and realized the housing was not a structural, load-bearing component. Strength was not the primary requirement; formability was. We recommended they switch to 3003-H14. The change was immediate and dramatic. Their production rate tripled, their scrap rate fell to nearly zero, and the final parts were exactly what they needed. They learned that choosing the right material is about matching the properties to the application, not just picking the "strongest" one.

So what is 3003 aluminum actually good for?

You have a new project, but you are overwhelmed by the number of aluminum alloys available. Choosing the wrong one means wasting money on a material that is too strong or too weak.

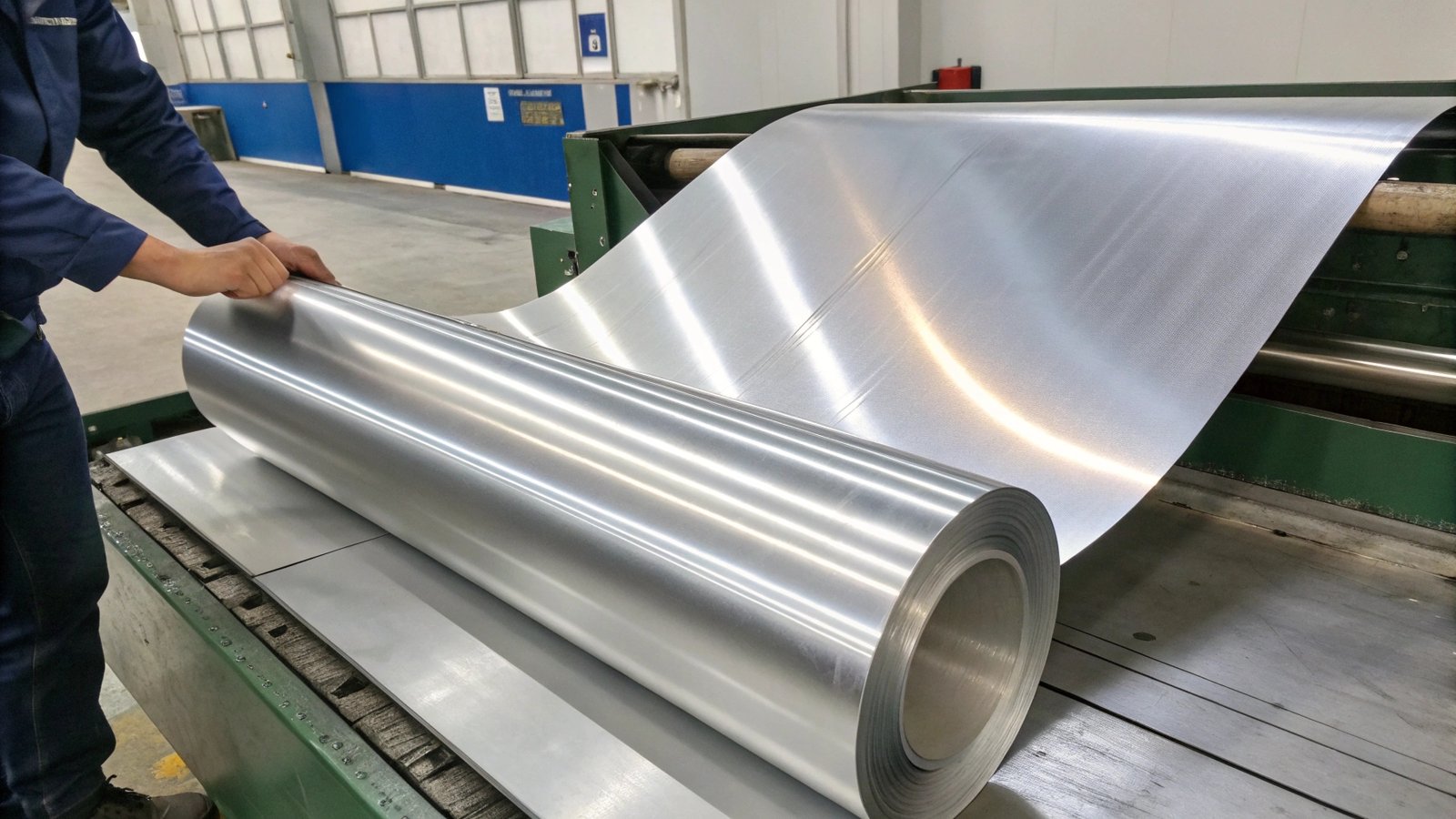

3003 is perfect for any application that requires excellent formability, good corrosion resistance, and moderate strength. Its most common uses include fuel tanks, heat exchangers, chemical equipment, and general sheet metal work.

Alloy 3003 finds its home where its specific combination of properties can shine. It is not an alloy for high-stress, structural parts. Instead, it is the champion of fabrication. Because it can be easily bent, spun, drawn, and welded, it is the preferred material for making things that need to hold liquids or transfer heat. For example, its excellent corrosion resistance makes it ideal for chemical storage tanks and piping. In the automotive world, its ability to be formed into complex shapes with thin walls makes it perfect for radiators and air conditioning evaporators. It is also widely used for cooking utensils, roofing, and siding. In all these cases, the material needs to be shaped easily and resist the environment. High strength would not only be unnecessary but would make manufacturing these products much more difficult and expensive. It is the go-to material when the manufacturing process is the biggest challenge.

Is 3003 aluminum truly formable?

You need to manufacture a component with deep draws and tight bends. You are worried that the material will crack or tear during the forming process, leading to high scrap rates and production costs.

Yes, 3003 has excellent formability. Its low strength and high ductility mean it can be easily stretched, bent, and shaped into complex geometries without fracturing, making it ideal for stamping and drawing operations.

The exceptional formability of 3003 aluminum is its defining characteristic. This comes directly from its simple metallurgy. It is essentially commercially pure aluminum (the 1100 series) with a small amount of manganese added. This single addition provides a modest increase in strength over pure aluminum but does not introduce the complex internal structures that make high-strength alloys like 6061 so hard and brittle. The result is a material that remains soft and ductile. This ductility allows the metal to stretch and flow easily under the pressure of a die or a press brake. It can be bent back on itself or drawn into the shape of a deep pan without the risk of cracking that you would face with a heat-treatable alloy. This is why it is so dominant in industries that rely on high-volume stamping, such as cookware and food packaging. Its ability to take a shape reliably is its greatest strength.

Does 3003 aluminum work harden?

You are forming a 3003 aluminum part and notice it is becoming stiffer and harder to bend with each operation. You're concerned that the material will become too brittle to complete the job.

Yes, 3003 is a non-heat-treatable alloy that gets its strength entirely through work hardening, also known as strain hardening. The more it is bent, rolled, or formed, the stronger and less ductile it becomes.

Understanding work hardening is key to working with 3003 aluminum. Unlike heat-treatable alloys like 6061, you cannot make 3003 stronger by putting it in an oven. Its strength comes from physically working the metal. When you bend or roll the aluminum, you are deforming its internal crystal structure. These crystals, or grains, get tangled and compressed, which makes it more difficult for them to move. This resistance to movement is what we measure as increased strength and hardness. This is the basis for the "H" tempers. For example, 3003-O is the fully soft, annealed state. 3003-H14 is strain-hardened to a half-hard temper, and 3003-H18 is strain-hardened to a full-hard temper. It is important to choose the right starting temper for your job. If you need to do a lot of extreme forming, you should start with the soft "O" temper. If you need a bit more strength in the final part and are only doing moderate bending, H14 is often the perfect choice.

Is 3003 H14 aluminum bendable?

You have a sheet of 3003-H14 and need to make a sharp 90-degree bend. You see the "H14" temper and worry that this "half-hard" state means the material is too brittle and will crack.

Yes, 3003-H14 is highly bendable. The H14 temper offers the perfect compromise between the dead-soft 'O' temper and the full-hard 'H18' temper, providing increased stiffness while retaining excellent formability for most applications.

The H14 temper is arguably the most popular and versatile temper for 3003 aluminum for a reason. It truly hits the sweet spot for general fabrication. Let's break down the temper designations to understand why.

Understanding H-Tempers

The "H" means the alloy is strain-hardened. The first digit "1" means it is strain-hardened only. The second digit indicates the final degree of strain hardening.

- H18: Full-hard. Has been work-hardened to its maximum practical strength. Bending can be difficult.

- H14: Half-hard. Has been work-hardened to a point midway between soft and full-hard.

- H12: Quarter-hard.

- "O" Temper: Fully annealed, or dead soft. Maximum formability, minimum strength.

For most sheet metal jobs, the O temper is too soft and easily damaged, while the H18 temper can be too brittle for tight bends. 3003-H14 provides a noticeable increase in strength and rigidity over the O temper, which is great for finished parts, but it has not been worked so much that it loses its excellent bendability. It can typically be bent back on itself in thinner gauges without cracking, making it a reliable and predictable material for fabricators.

Conclusion

Choose 3003 aluminum when formability is your goal. This versatile workhorse provides the perfect, cost-effective solution for complex shapes where extreme strength is not required, ensuring successful and efficient fabrication.