You are choosing a material and face a confusing choice: aluminum or alloy? This leads to picking the wrong material, causing part failure and costing you time and money.

This is a false choice. Pure aluminum is a soft element, a raw ingredient. An aluminum alloy1 is that element engineered for a mission. We add elements like copper for strength or magnesium for corrosion resistance2. You don't buy the ingredient; you buy the engineered performance.

I’ll never forget a call from a potential client, a trader new to the metals industry. He wanted a price for a large quantity of "pure aluminum discs" for one of his machining customers. I was a bit surprised. I asked him what the final parts would be used for. He said they were for structural plates on a piece of industrial machinery. I had to pause and explain that pure aluminum is incredibly soft. It would deform under the machine's own weight. It was the wrong choice for his customer. He was thinking of aluminum as a single thing, like steel. I explained that what he really needed was an aluminum alloy, like 6061-T63, which is engineered for exactly that kind of structural strength. He was relieved. We helped him look like an expert to his customer and supplied the right material for the job. This taught me that our most important job isn't just selling metal; it's helping our clients understand they are buying a solution, not just an ingredient.

Are alloy and aluminum actually the same thing?

The words "aluminum" and "alloy" are used interchangeably in conversation. This creates confusion when you need to place a precise order, leading to getting the wrong material.

No, they are not the same. Pure aluminum is a chemical element (Al). An aluminum alloy is a mixture where aluminum is the main ingredient, but it's enhanced with other elements like magnesium or silicon to dramatically improve its properties.

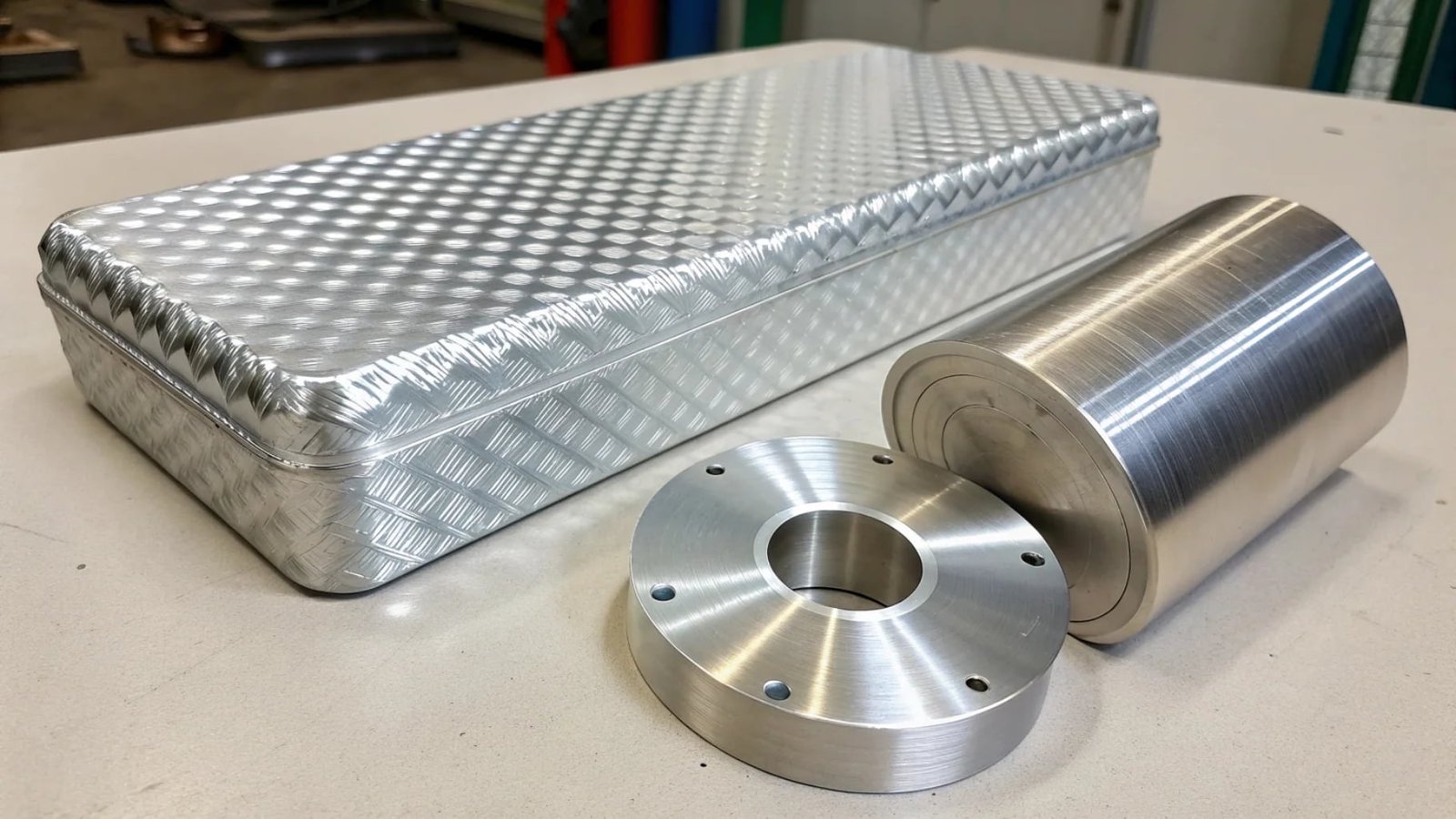

Think of it like this: pure aluminum is flour. You wouldn't use only flour to bake a strong, delicious cake. You need to add other ingredients like eggs, sugar, and baking powder. An aluminum alloy is the finished cake mix, perfectly blended for a specific outcome. For our machining customers, this distinction is everything. Machining pure aluminum is a gummy, difficult process, and the final part would be almost useless structurally. Machining an aluminum alloy like 6061 or 7075 is predictable and efficient, and the final part has the exact strength and hardness it was designed for. Understanding this fundamental difference is the first step to sourcing high-performance components.

From Raw Element to Engineered Material

The properties change dramatically when you move from the pure element to an engineered alloy.

| Property | Pure Aluminum (99.5%) | 6061-T6 Aluminum Alloy |

|---|---|---|

| Main Components | Aluminum (Al) | Aluminum (Al), Magnesium (Mg), Silicon (Si) |

| Strength (Tensile) | Very Low (~90 MPa) | Good (~310 MPa) |

| Hardness | Very Soft | Hard |

| Best Use Case | Electrical wiring, foil | Structural parts, machine components |

| Analogy | Raw flour | A complete cake mix |

As you can see, the alloy is over three times stronger. This strength doesn't come from the aluminum itself, but from the way the added elements interact within the metal's crystal structure, especially after our forging and heat treatment processes.

Will my aluminum alloy parts get rusty?

You see some discoloration on an aluminum part and worry it is rusting like steel. This can cause you to discard a perfectly good component, assuming it has failed from corrosion.

No, aluminum alloys do not rust. Rust is specifically iron oxide, which forms on steel. Aluminum alloys can corrode, but they do so by forming a tough, protective layer of aluminum oxide that actually prevents further corrosion.

This is a key advantage that we often highlight to our clients in the Middle East, where high humidity and coastal air can be a big problem. When steel rusts, the rust flakes off and exposes fresh metal underneath, allowing the corrosion to eat deeper and deeper until the part fails. Aluminum is much smarter. When it is exposed to oxygen, it instantly forms a very thin, hard, transparent layer of aluminum oxide on its surface. This layer is passive, meaning it doesn't react with the environment. It acts like a permanent, self-repairing coat of paint that seals the metal from further attack. If you scratch it, a new protective layer forms immediately. This is why our 5083 forged rings are so popular for marine applications; they are engineered to use this natural property to their advantage.

Corrosion vs. Rust

While the words are often used together, the processes are very different.

- Rust (Iron/Steel): An aggressive, destructive process. The iron oxide (rust) is porous and flakes away. This continually exposes new metal to oxygen and moisture, and the corrosion continues until the metal is gone. It is a sign of failure.

- Corrosion (Aluminum): A self-protecting process. The aluminum oxide layer is hard, non-porous, and strongly bonded to the surface. It stops the corrosion process completely. In most cases, it is a sign of the material doing its job.

For applications requiring extreme corrosion resistance, we recommend alloys from the 5000 series. These alloys, which contain magnesium, form an even more robust protective oxide layer, making them ideal for saltwater and harsh chemical environments.

Is alloy steel the same as aluminum?

You are sourcing materials and see the terms "alloy" and "aluminum alloy." This can make you think "alloy steel" and "aluminum alloy" are similar, leading to massive errors in design and ordering.

No, they are completely different materials. "Alloy steel" is steel (mostly iron) mixed with other elements. "Aluminum alloy" is aluminum mixed with other elements. The only thing they have in common is that they are both alloys.

This confusion is dangerous because the properties of these two materials could not be more different. We had a client, a trader, who nearly made this mistake. His customer's drawing just said "high-strength alloy" for a part on a high-speed rotating machine. He almost quoted them for a common alloy steel. We asked for more details and realized the main goal was low weight to reduce inertia. Alloy steel is almost three times denser than aluminum alloy. Using it would have tripled the part's weight, requiring a much larger motor and potentially causing the machine to vibrate itself apart. We recommended a forged 7075 aluminum alloy instead. It provided similar strength at a fraction of the weight. It's a perfect example of why you must know the base metal. "Alloy" just means it's a mix; it doesn't tell you what the main ingredient is.

Two Different Worlds

| Property | Alloy Steel (e.g., 4140) | Aluminum Alloy (e.g., 6061-T6) |

|---|---|---|

| Base Metal | Iron (Fe) | Aluminum (Al) |

| Density | High (~7.85 g/cm³) | Low (~2.70 g/cm³) |

| Strength | Very High | Good to High |

| Corrosion | Rusts easily, needs coating | Excellent corrosion resistance |

| Machinability | More difficult, slower speeds | Excellent, high-speed machining |

| Primary Advantage | Extreme hardness and toughness | Excellent strength-to-weight ratio |

Choosing between them depends entirely on the mission. If you need extreme wear resistance and can handle the weight, steel is the answer. If you need good strength but weight is your enemy, aluminum alloy is the clear winner.

Conclusion

Stop asking "aluminum or alloy?" Instead, ask "what is the mission for my part?" This helps you choose the right engineered aluminum alloy for the strength, corrosion resistance, or low weight you need.